By Tony Chapelle

Investors and corporate America now generally accept the proposition that environmental, social and governance factors have a material impact on companies’ performance and risks. Yet the way that many businesses disclose their ESG behavior remains helter-skelter.

Agenda commissioned stock-ratings company HIP Investor to identify the S&P 500 companies that most fully — and least fully — report these important metrics that connect with financial value creation and risk reduction.

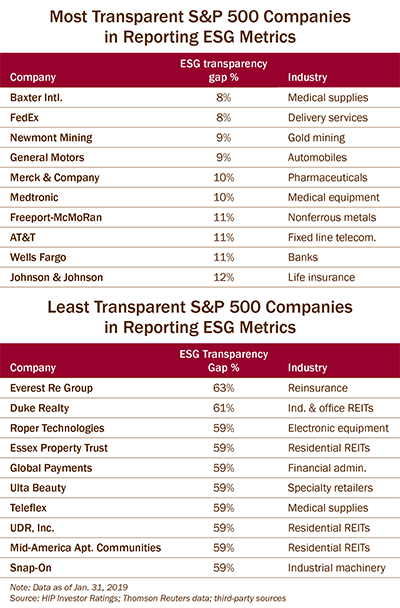

HIP found that the 10 most ESG-transparent companies included Baxter International, FedEx, Newmont Mining, General Motors and, maybe surprisingly given its surfeit of customer abuse problems, Wells Fargo. This most transparent group hailed from an array of industries.

On the other hand, half of the 10 least ESG-transparent companies came from the financial sector and, more specifically, industries such as real estate investment trusts and insurance. They included Everest Re Group, Duke Realty, Roper Technologies, Ulta Beauty and Snap-On.

The rankings don’t mean that transparent companies, for instance, are engaging in better ESG behavior than other companies. It means they set, describe and publish sustainability goals that advance their corporate strategies, generally meet those targets, and report what they’ve done.

“Increasingly, investors expect these so-called non-financial parameters to be reported because they do have financial impact. That’s an unmistakable trend,” says Paula DiPerna, an expert on carbon pricing and a special advisor at the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP). The CDP is the nonprofit organization that 15 years ago started asking companies, cities, states and regions to disclose their environment-related metrics and initiatives so that investors and policymakers could evaluate them. Last year, more than 7,000 corporations submitted that data to the CDP.

HIP analyst Erik Nielsen evaluated which companies had higher transparency by analyzing their CDP disclosures, company annual reports, corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports, sustainability reports and the Thomson Reuters/Refinitiv database. (To be sure, not all companies produce CSR or sustainability reports.)

From all of these sources, Nielsen gathered 300 raw ESG data points on items including water usage and efficiency, employee engagement and carbon emissions.

For instance, in 2010, under the Obama administration, the Securities and Exchange Commission staff stated that publicly traded companies ought to disclose financially material impacts related to climate change, including costs to comply with regulations on greenhouse gas emissions.

Under the Trump administration, however, the SEC is not mandating that all such material risks be disclosed, says HIP CEO Paul Herman. “So, investors are at more risk because some companies are not disclosing.

Here are some of the companies that scored highest for ESG-disclosure transparency, and why:

Baxter International

The plasma and vaccine provider led the field with the smallest transparency gap, just 8%. Among the reasons Baxter scores so high for its disclosures is that it offers an overview of the material sustainability issues it faces in accordance with guidelines of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, a group that has created guidelines to introduce ESG factors into financial accounting. In addition, the company provides a sustainability data summary with a three-year history of ESG data in order to track the company’s progress.

FedEx

The world’s largest private logistics company provides an 11-page appendix to its sustainability report with all of its ESG data.

Newmont Mining

Given the highly detrimental environmental impact of the mining business, Newmont provides a series of reports related to ESG. The firm has a general sustainability report, a separate report on community relationships and an additional one for conflict-free gold.

Meanwhile, companies that were identified as least transparent often failed to disclose a litany of topics about their ESG behavior:

Everest Re Group

Bermuda-based reinsurance firm Everest was the largest company among the worst-reporting group, at $7 billion in annual revenue. The NYSE-listed outfit chose not to report nearly two thirds of what it could have compared to the most transparent S&P 500 companies. The areas on which Everest remained silent included salaries and wages, water withdrawal total, lobbying and political contributions and staff composition by gender.

Duke Realty

The Indianapolis-based REIT for industrial warehouses was the runner-up for releasing the smallest amount of useful information, just 61% of what some of its S&P 500 compatriots do. Duke didn’t publish data about at least 17 subjects including turnover of employees, total direct and indirect energy consumption, CO2 equivalents emission total, waste total, water recycled and lobbying and political contributions.

Snap-On

The $4 billion toolmaker and rental company from Kenosha, Wis., was tied with eight companies that failed to disclose 59% of potential ESG information. Snap-On sat on data about lost-time injury rate, resource reduction vs. materials used, freshwater withdrawal total, lobbying and political contributions and female representation in management.

The metrics that make up the transparency gap score were derived from six general ESG pillars. Those pillars comprise management practices, health, wealth, earth, equality and trust.

Within each of those categories are several metrics such as financials (under management practices), job safety (under health) and CEO compensation compared to employee compensation (under wealth).

“The main difference between the most and the least transparent companies is that the most transparent provide the most substantial data in their sustainability reports’ appendices. Those are written to convey a story,” Nielsen says.

“Readers [can] compare these numbers that can be assessed, correlated and used to identify risk-adjusted returns.”

Another thing Nielsen points out about leading transparent companies is that they hire third parties such as Bureau Veritas to inspect and certify their numbers. Also, the leaders all participate in the Carbon Disclosure Project, which not only provides a standardized ESG questionnaire but publishes the sustainability data where any investor can access it.

On the other hand, the companies with the biggest transparency gaps sometimes mention sustainability policies on their websites or submit sustainability reports, but without numbers. They refer to plans, but those are not quantifiable, nor can they be corroborated by investors. Or sometimes they report numbers, but in text, not appendices that are accessible.

And some companies are making changes. For example, after Agenda contacted Mid-American Apartment Communities to notify officers and the board that the company would be named on the list, a spokesperson responded in an e-mail that for years the company has engaged in ESG initiatives but did not publicize those efforts.

Jennifer Patrick wrote that Mid-American has now hired a leading sustainability data management vendor to identify and collect reliable information for disclosure.

She said the company will also produce its first sustainability report next year.

Why hasn’t anyone achieved 100% transparency? Few companies provide hard numbers for every data point, or they may disclose using a qualitative statement. In other instances, firms don’t disclose ESG issues that may not be financially material for them.

Are the laggard companies trying to hide or just not following best practices? Nielsen says he’s not in a position to say. “But it would make sustainable investors more comfortable if companies would disclose sustainability information.”

This article originally appeared in Agenda on April 9, 2019.